Two engineers are standing by a river. One says, “Look at that beautiful laminar flow.” The other replies, “Actually, it’s unsteady and rotational near the bank.” They’re not speaking different languages—they’re using the essential vocabulary of fluid mechanics. These five classification pairs are the difference between guessing what’s happening and knowing exactly what you’re seeing.

Fluid mechanics is built on five fundamental classification pairs. These aren’t just academic terms, they’re practical tools that tell engineers which equations to use, what measurements to take, and how to predict system behavior. Here are the definitions, explanations, and applications you need to master.

1. Steady vs. Unsteady Flow

Steady flow is a flow in which the averages of flow parameters like velocity, pressure, and density do not change with time at any fixed point in the flow field. Mathematically, for any flow property φ, ∂φ/∂t = 0 at every point.

Unsteady flow (also called transient flow) is a flow in which flow parameters change with time at fixed points in the flow field. Mathematically, ∂φ/∂t ≠ 0.

Examples:

- Steady: Water flowing through a pipe at constant rate

- Unsteady: Blood pulsing through arteries (each heartbeat changes the flow)

- Periodic unsteady: Vortex shedding behind a cylinder

Why it matters: Steady flows are mathematically simpler. The Navier-Stokes equations lose their time derivative terms, making them easier to solve. Most engineering analyses start by assuming steady flow unless there’s clear evidence of unsteadiness.

How to identify: Place a velocity probe at a fixed point. If the reading remains constant over time, the flow is steady at that point. If it fluctuates, the flow is unsteady.

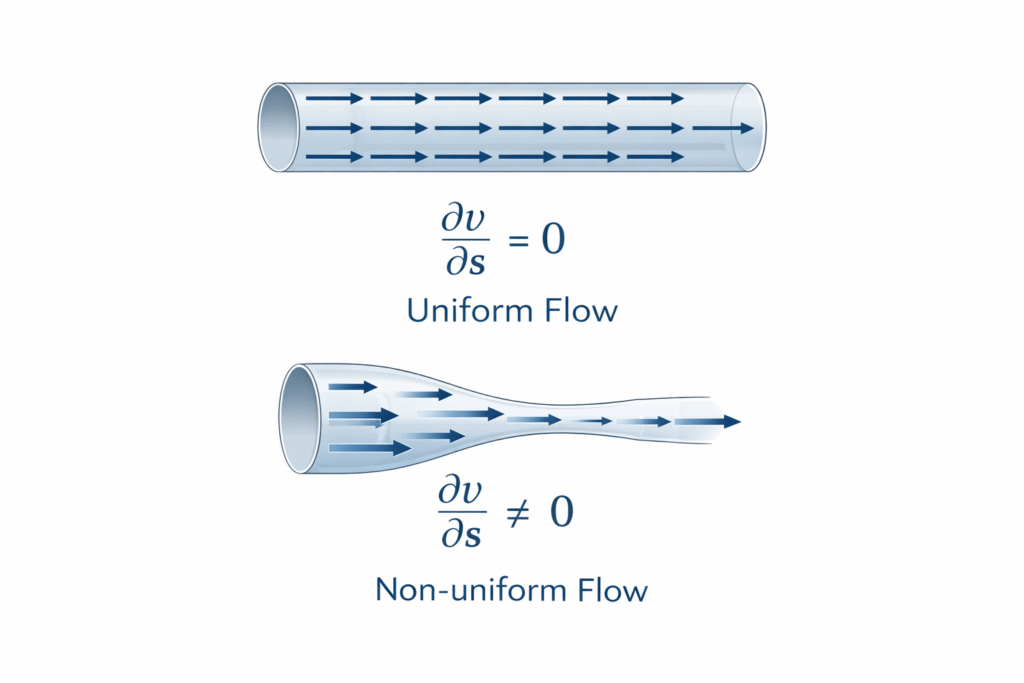

2. Uniform vs. Non-uniform Flow

Uniform flow is a flow in which the velocity vector (both magnitude and direction) is identical at every point in the flow field at a given instant. Mathematically, the spatial gradient ∂v/∂s = 0 along a streamline.

Non-uniform flow is a flow in which the velocity changes from point to point in the flow field at a given instant. Mathematically, ∂v/∂s ≠ 0.

Examples:

- Uniform: Water flowing in a long, straight pipe of constant diameter

- Non-uniform: Flow through a nozzle (accelerating), diffuser (decelerating), or bend (changing direction)

Why it matters: In non-uniform flows, fluid particles experience convective acceleration even if the flow is steady. This affects pressure distribution and requires more complex analysis.

How to identify: Measure velocity at multiple points along a streamline. If all measurements show the same velocity, the flow is uniform. If velocities differ, it’s non-uniform.

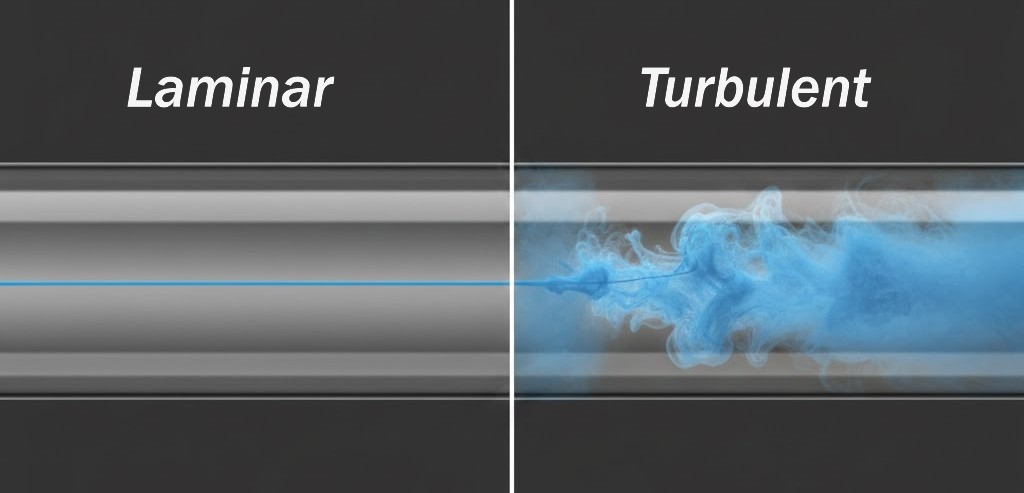

3. Laminar vs. Turbulent Flow

Laminar flow is a flow in which fluid particles move in smooth, parallel layers (laminae) without mixing between layers. The flow is orderly and predictable.

Turbulent flow is a flow in which fluid particles move in irregular, chaotic paths with significant mixing between layers. The flow exhibits random fluctuations and eddies.

The deciding factor: The Reynolds Number (Re = ρVD/μ)

- Re < 2,300: Typically laminar (for pipe flow)

- 2,300 < Re < 4,000: Transition region

- Re > 4,000: Typically turbulent (for pipe flow)

Examples:

- Laminar: Honey pouring slowly, blood flow in capillaries

- Turbulent: River rapids, air flow in ventilation ducts

Why it matters: Turbulent flows have much higher friction losses (requiring more pumping power) but also better mixing and heat transfer. Laminar flows have lower losses but are prone to separation.

How to identify: Inject dye into the flow. In laminar flow, the dye stays in a thin, straight line. In turbulent flow, the dye quickly mixes throughout the flow.

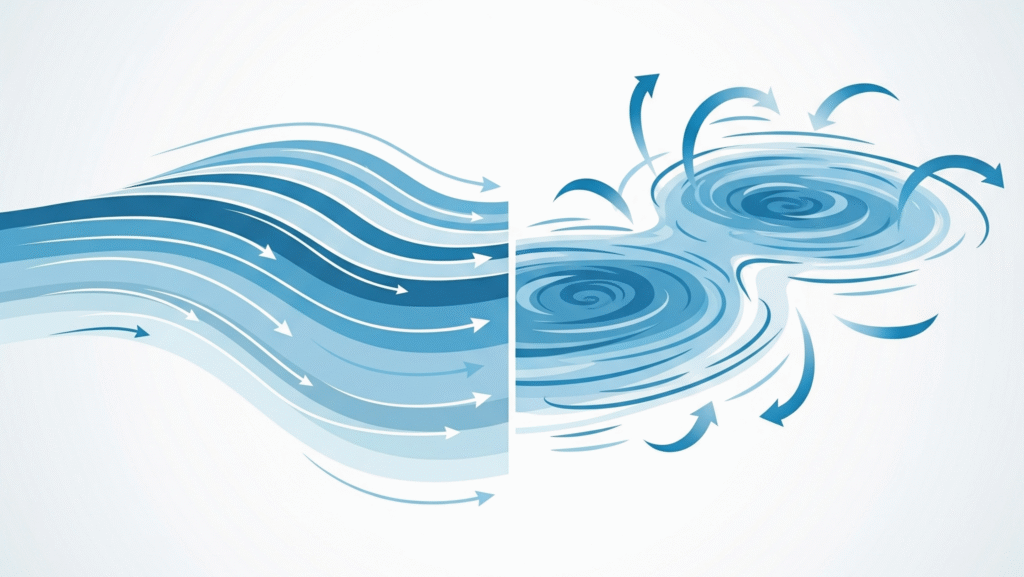

4. Rotational vs. Irrotational Flow

Rotational flow is a flow in which fluid particles rotate about their own axes as they move along their paths. Mathematically, the vorticity ω = ∇ × v is non-zero.

Irrotational flow is a flow in which fluid particles do not rotate about their own axes as they move. They may translate and deform, but they don’t spin. Mathematically, ω = ∇ × v = 0.

Examples:

- Rotational: Water in a stirred cup, boundary layer flow near a surface

- Irrotational: Flow around an airfoil (outside the boundary layer), potential flow solutions

Why it matters: Irrotational flows are mathematically much simpler. They can be described by potential functions, allowing solutions without solving the full Navier-Stokes equations. Rotational flows require more complex analysis.

The paradox: A draining bathtub vortex is often irrotational—water moves in circles but individual particles don’t spin about their own centers.

How to identify: Place a small paddle wheel in the flow. If it rotates, the flow is rotational. If it translates without rotating, the flow is irrotational.

5. Compressible vs. Incompressible Flow

Compressible flow is a flow in which the density of the fluid changes significantly due to pressure and temperature variations. Density is treated as a variable.

Incompressible flow is a flow in which density remains essentially constant throughout the flow field. Density is treated as a constant.

The deciding factor: The Mach Number (Ma = v/a, where a is speed of sound)

- Ma < 0.3: Typically treated as incompressible (density changes < 5%)

- Ma > 0.3: Must consider compressibility effects

Examples:

- Compressible: Air flow over aircraft at high speeds, gas flow in pipelines

- Incompressible: Water flow in pipes, most low-speed air flows

Why it matters: Incompressible flow equations are simpler (continuity equation becomes ∇·v = 0). Compressible flows require considering energy equations and can experience shock waves.

How to identify: Calculate the Mach number. If Ma < 0.3, incompressible assumption is usually valid. For liquids, the incompressible assumption is generally valid unless dealing with water hammer or cavitation.

Key Relationships Between Classifications

Understanding how these classifications interact is crucial:

- Turbulent flows are almost always rotational (the eddies create vorticity)

- Most real flows are unsteady to some degree, but we often approximate them as steady

- Compressibility effects become important at high speeds (high Mach numbers)

- Viscous flows near boundaries are always rotational

- Potential flow theory assumes incompressible, irrotational flow

Practical Engineering Applications

When to use which approximation:

| Application | Likely Classifications | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Pipe flow design | Steady, incompressible, turbulent | Most industrial applications |

| Aircraft wing design | Initially: incompressible, irrotational | Preliminary design phase |

| Microfluidic devices | Laminar, incompressible | Small scale → low Reynolds numbers |

| High-speed aerodynamics | Compressible, turbulent | High Mach numbers |

| Blood flow analysis | Unsteady, incompressible, often laminar | Pulsatile nature, small vessels |

Common Misconceptions

Myth 1: “All high-speed flows are turbulent.”

Truth: You can have high-speed laminar flow with proper boundary layer control.

Myth 2: “Circular motion means rotational flow.”

Truth: A free vortex (v ∝ 1/r) is irrotational despite circular streamlines.

Myth 3: “Liquids are always incompressible.”

Truth: Water hammer and cavitation show liquids can exhibit compressibility effects.

Myth 4: “Uniform flow means simple geometry.”

Truth: Achieving truly uniform flow in experiments requires careful design.

Myth 5: “Steady flow means no acceleration.”

Truth: In non-uniform steady flow, particles accelerate when moving into faster regions.

Engineering Decision Framework

When facing any fluid mechanics problem:

- Check the Mach number → Is compressibility important?

- Calculate Reynolds number → Laminar or turbulent?

- Analyze time scales → Steady or unsteady?

- Examine geometry → Uniform or non-uniform?

- Consider boundary conditions → Rotational or irrotational?

These classifications tell you:

- Which equations to start with

- What simplifications you can make

- What phenomena to expect

- What measurements you need

Summary Table

| Classification | Key Parameter | Critical Value | Mathematical Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady vs. Unsteady | Time derivative | N/A | ∂φ/∂t = 0 (steady) |

| Uniform vs. Non-uniform | Spatial gradient | N/A | ∂v/∂s = 0 (uniform) |

| Laminar vs. Turbulent | Reynolds number | Re ≈ 2,300-4,000 | Re < 2,300 (laminar) |

| Rotational vs. Irrotational | Vorticity | ω = 0 | ∇ × v = 0 (irrotational) |

| Compressible vs. Incompressible | Mach number | Ma = 0.3 | Ma < 0.3 (incompressible) |

💡 Quick Reference Guide:

Next time you analyze a flow, ask:

- Time: Does it change with time? (Steady/Unsteady)

- Space: Does it change with position? (Uniform/Non-uniform)

- Order: Is it smooth or chaotic? (Laminar/Turbulent – check Re)

- Spin: Do particles rotate? (Rotational/Irrotational)

- Density: Does density change? (Compressible/Incompressible – check Ma)

Remember: Real flows are mixtures of these classifications. A river might be steady over minutes, non-uniform, turbulent, rotational, and incompressible. The engineering skill is knowing which classifications dominate for your specific problem.

🤔 Discussion Questions:

- In your experience, which flow classification is most frequently misunderstood or misapplied?

- Can you think of an engineering failure that resulted from incorrect classification of flow type?

- Which classification do you find most challenging to identify in practice?

📚 Learning Resources:

- Reynolds Number Without Equations: The Crowd vs. the River

- Mach Number Demystified: When Your Flow Starts to Feel the Squeeze

Share examples of how you’ve applied these classifications in your work or studies!