The Invisible Force Field: A Practical Guide to Boundary Layers

Here’s a question: Have ever watched a landslide or avalanche closely on a video (or maybe in person if you’re one of God’s favourites)? If you look closely you can observe that the topmost layer moves with the highest velocity and the speed decreases as one gets closer to the ground which is staionay .

This same thing happens in the case of fluids as well.

Think about air flowing over an airplane wing. You might picture smooth, straight streamlines. But right next to the surface, something fascinating happens. The fluid sticks to the wall, creating a thin, invisible region where its speed changes dramatically. We call this the boundary layer. Understanding it isn’t just academic—it’s the key to predicting drag, heat transfer, and even whether your flow will separate. Let’s break it down.

What is a Boundary Layer?

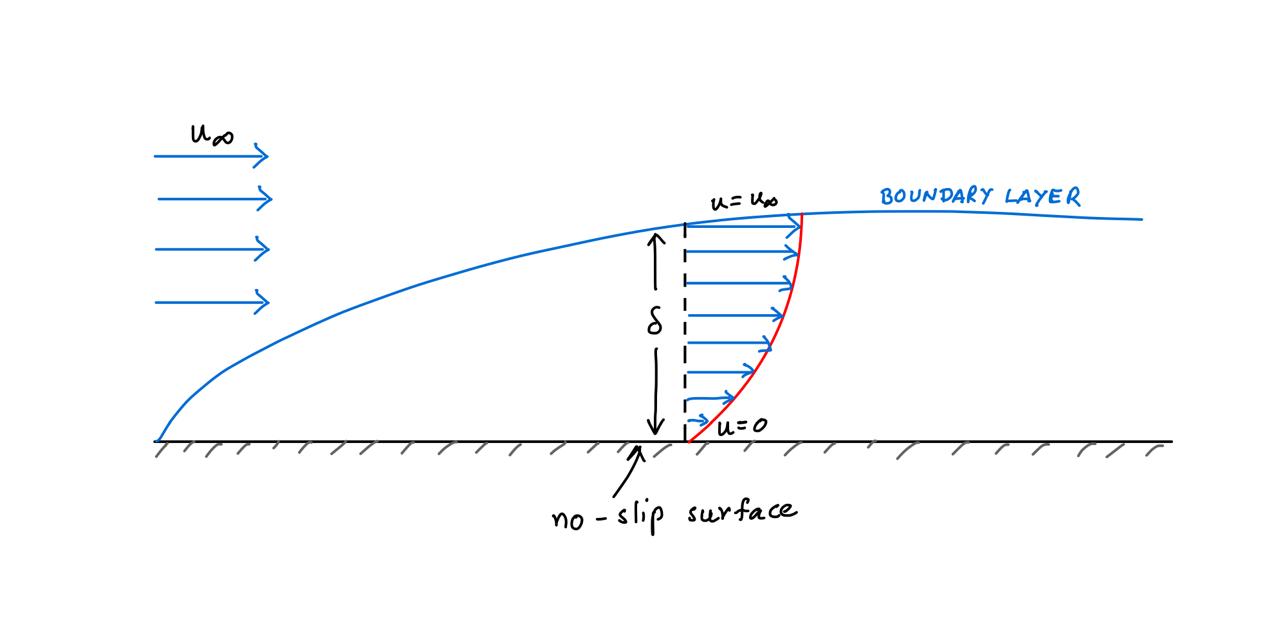

Simply put, the boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid close to a surface where viscous forces matter. Far from the wall, we can often ignore viscosity, treating air or water as “inviscid.” However, right at the surface, the fluid velocity must be zero—this is the no-slip condition.

As a result, the flow speed increases from zero at the wall to 99% of the freestream velocity at the boundary layer’s edge. This region of velocity change is our focus.

Why Should You Care?

The boundary layer might be thin, but it controls your simulation’s destiny. Specifically, it directly influences:

- Skin Friction Drag: The viscous shear within the boundary layer creates drag. A thicker layer or more turbulent flow often means higher drag.

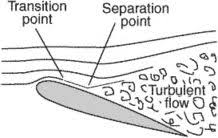

- Flow Separation: If the boundary layer slows down too much, it can detach from the surface. Consequently, this separation causes massive pressure drag, stall on wings, and vortex shedding.

- Heat Transfer: The steep temperature gradients exist primarily within the boundary layer. Therefore, accurately modeling it is essential for predicting heating and cooling.

Laminar vs. Turbulent:

Boundary layers come in two main flavors, and the difference is critical.

- Laminar Boundary Layer:

Smooth, orderly, and layered. It has lower skin friction drag but separates easily when faced with an adverse pressure gradient (a rising pressure that slows the flow down). - Turbulent Boundary Layer:

Chaotic, mixed, and energetic. It has higher skin friction drag near the wall, but its extra momentum makes it much more resistant to separation.

So, how does the transition happen? It starts with instabilities that grow into turbulent spots, which eventually merge. We often predict this using a Reynolds Number, a dimensionless value comparing inertial to viscous forces.

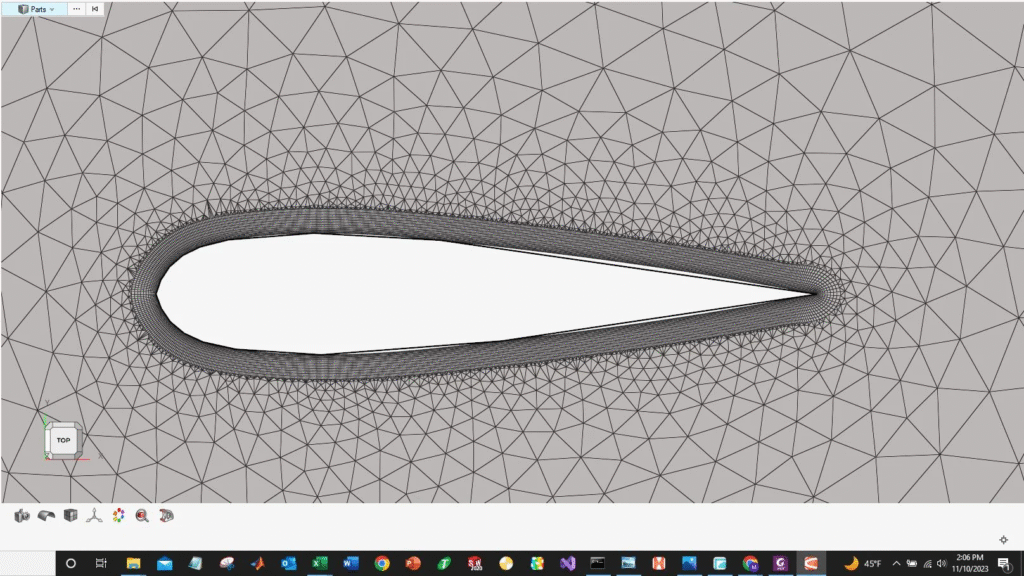

How to Resolve Boundary Layers in CFD: The Mesh is Key

If you want accurate results, your mesh must capture the boundary layer. Here’s how:

- Use Inflation Layers:

Always use structured, orthogonal “inflation layers” at your walls. Never rely on a coarse, triangular mesh to resolve these critical gradients. - Master the Y+ Value:

Y+ is the most important parameter here. It’s a non-dimensional distance from the wall that dictates your wall modeling approach. It basically measures distance from the nearest wall in viscous units (dimensionless). For example, Y+ = 1 means the flow in the cell is in the viscous sub-layer whereas, increasing Y+ (around >30) means the flow in the cell is far engough from the wall to not be influenced by the no-slip condition at the wall.- Y+ ≈ 1 (Wall-Resolved): Your first cell is inside the viscous sublayer. This approach is accurate but computationally expensive because you need many very fine mesh layers.

- 30 < Y+ < 300 (Wall-Modeled): Your first cell is in the log-law region. You use a “wall function” to bridge the gap between the wall and your first cell. This method is much less expensive and often sufficient for industrial applications.

Your Practical CFD Checklist

Before you run your next simulation, ask yourself:

- Did I apply inflation layers to all no-slip walls?

- What is my target Y+ value? (Choose based on your turbulence model’s requirements).

- Does my mesh have enough layers to fully resolve the boundary layer’s growth?

- Am I using the appropriate turbulence model (e.g., k-omega SST for accurate separation predictions)?

The Bottom Line

The boundary layer is the ultimate gatekeeper. It decides your drag, predicts your separation, and governs your heat transfer. By thoughtfully meshing and modeling this invisible force field, you move from getting a result to getting the right result.

Got a tricky case involving flow separation or heat transfer? Share your boundary layer challenges in the comments below!

Further Reading: