The “0.001 Second” difference—the blink of an eye that separates the front row from the midfield—is not found on the track. It is found in the server room.

For decades, Formula 1 was an engine formula. But in the 2021 title fight that defined the modern era, the war was won by code. This is the story of how Red Bull Racing weaponized Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to break Mercedes’ seven-year stranglehold, and the engineering reality behind the “invisible war.”

The 0.0001 second problem

At 200 mph, air isn’t just gas; it’s a solid wall. An F1 car doesn’t just slice through it—it violently reorders the atmosphere to suck the car into the asphalt.

The engineering challenge is not “drag reduction.” It is wake management.

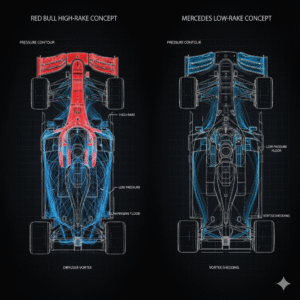

Every rotating wheel creates a chaotic mushroom cloud of “dirty air” (turbulence) that destroys the efficiency of the rear wing and diffuser. The goal is to seal the floor edges and punch a clean hole through the air, keeping the tire wake away from the downforce-generating bodywork.

The Scale: A change in the front wing endplate angle by 1 millimeter can alter the airflow structure 3 meters further back, potentially stalling the diffuser.

The Stakes: A 0.5% gain in aerodynamic efficiency (L/D) is worth roughly 0.1 seconds per lap. In qualifying, that is the difference between Pole Position and P4.

The 2021 CFD Arms Race

Entering 2021, new regulations sliced away a triangular portion of the floor to slow the cars down. This was a crisis for the “Low Rake” concept (Mercedes), which relied on a long floor to seal the air.

Red Bull ran the “High Rake” concept (nose down, rear up). To save their season, they had to prove their concept could survive the floor cut. They couldn’t just guess; they had to simulate billions of air particles.

The Oracle Partnership & The Compute Spike:

Red Bull partnered with Oracle to overhaul their simulation pipeline. By moving to cloud infrastructure (ARM-based servers), they didn’t just get faster computers; they changed how they worked.

- Throughput: Increased simulation runs by 1,000×

- Latency: Simulation speed jumped by 25%, allowing engineers to test a new front wing design in the morning and have the data by lunch

This allowed Red Bull to “brute force” the 2021 regulations, running thousands of floor edge iterations to find the one geometry that recovered the lost downforce. While Mercedes struggled with rear-end instability in pre-season testing, Red Bull’s digital prediction held true.

The Engineering Core – Meshing & Solvers

How do you simulate a hurricane inside a computer? You break the air into tiny cubes. This is Meshing, and it is where the simulation lives or dies.

F1 teams don’t just “run the software.” They operate at the bleeding edge of the Navier-Stokes equations, solving the math of fluid motion. Here’s a quick primer on the universal rules that also govern the creation of a championship-winning CFD model:

The “Y+” Obsession

The most critical battleground is the Boundary Layer—the thin strip of air (less than 1mm thick) clinging to the car’s surface.

- Viscous Sublayer: Right against the carbon fiber, air molecules are sticky. To simulate this accurately, the mesh cells must be microscopic.

- The Metric: Engineers obsess over the Y+ value (a non-dimensional wall distance). For high-fidelity F1 simulation, you target a Y+ ≈ 1. This ensures you are solving the physics of the viscous sublayer directly rather than using a “wall function” (an approximation).

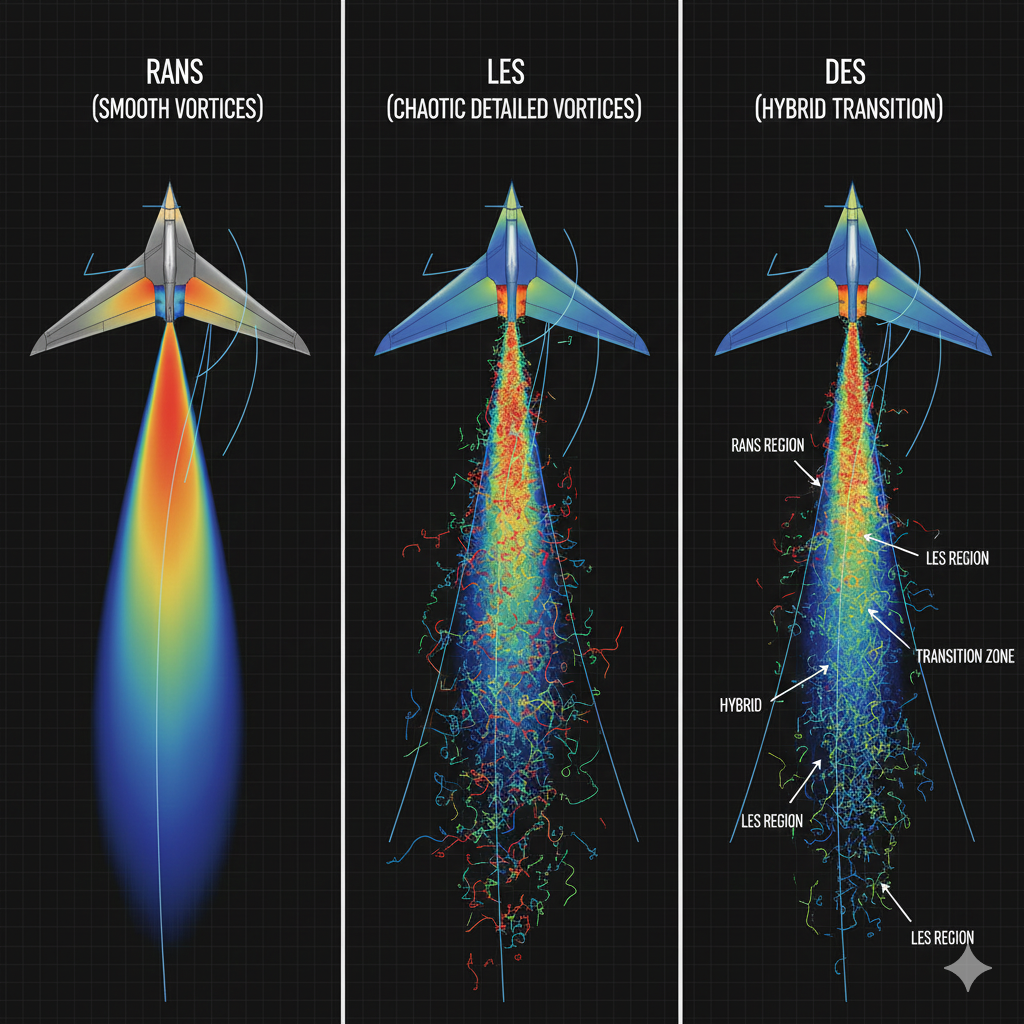

The Solver: Hybrid RANS-LES (DES)

You cannot solve every eddy of turbulence (DNS – Direct Numerical Simulation) because it would take a supercomputer 100 years to solve one lap.

Red Bull, like most top teams, uses a hybrid approach called DES (Detached Eddy Simulation):

- Near the Car (RANS): Uses Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes equations. It’s stable and cheaper. Good for attached flow.

- In the Wake (LES): Uses Large Eddy Simulation. As soon as the air detaches (like off the rear wing), the solver switches to LES to accurately model the chaotic, swirling vortices.

The Tool: Red Bull utilizes Ansys Fluent, leveraging specific “Mosaic” meshing technology that automatically stitches together high-quality hex-dominant meshes (for accuracy) with polyhedral meshes (for speed) in the bulk flow.

Validation – The “Map vs Territory” Problem

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

The nightmare scenario for an Aerodynamicist is Correlation Failure. This happens when the CFD says “20 points of downforce,” the Wind Tunnel says “18 points,” and the driver says “the car is undrivable.”

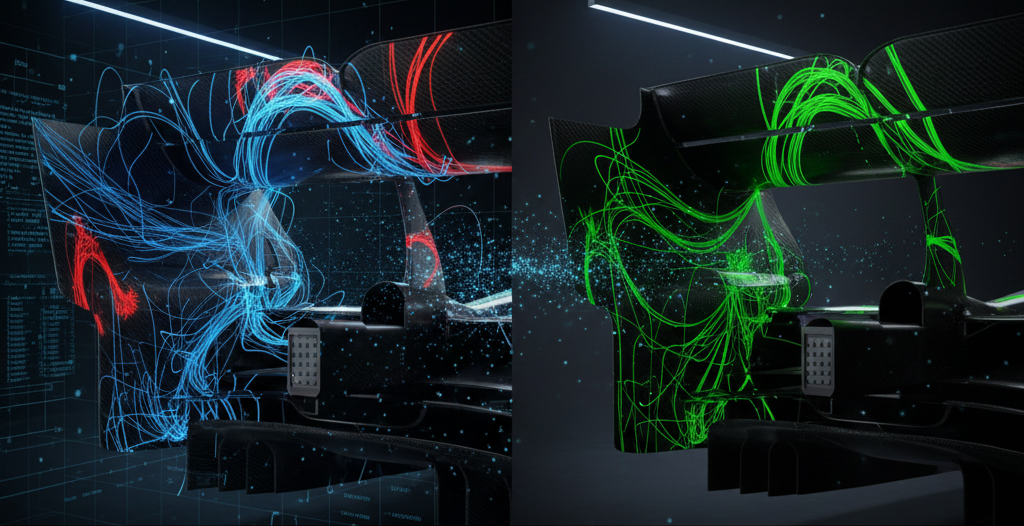

To validate the “Map” (CFD), teams use the “Territory” (Track Data).

The Aero Rake: You’ve seen these in testing—massive metal fences bolted to the car. They are arrays of Kiel Probes. Unlike standard pitot tubes, Kiel probes are shrouded, allowing them to measure total pressure accurately even when the air is hitting them at an angle (yaw).

Flow-Vis Paint: A fluorescent powder mixed with paraffin oil. It streaks along the car, physically showing the streamlines.

The Loop: If the neon green paint on the track doesn’t match the neon streamlines on the monitor, the model is broken. In 2021, Red Bull’s correlation was nearly perfect; the RB16B behaved exactly as the servers predicted.

The Ethical Question & Success Handicap

Is it fair that the team with the best computers wins?

F1 decided “No.”

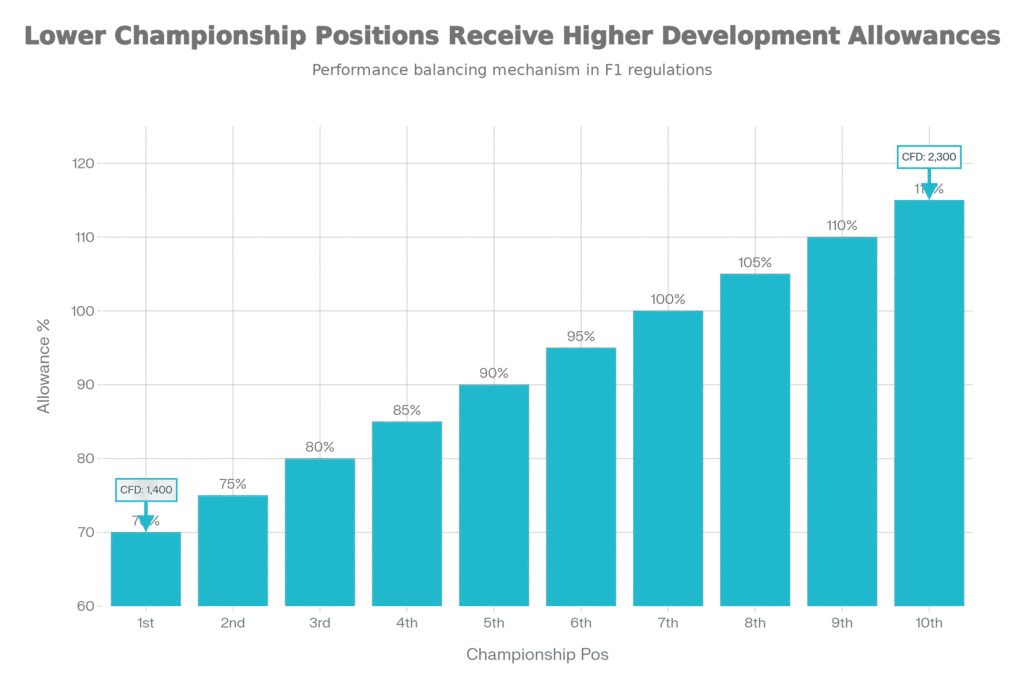

To prevent a spending war, the FIA introduced the ATR (Aerodynamic Testing Regulations). It is a sliding scale handicap system.

The Rule: The better you finish, the less CFD time you get next year.

The Impact: As the 2021 Champion, Red Bull was slashed to 70% of the baseline CFD allowance, while the last-place team got 115%.

The New Reality:

Red Bull isn’t winning today because they have more CFD time. They are winning because their 2021 infrastructure upgrade made them more efficient. They can run fewer simulations, but those simulations are higher quality (better meshing, better solvers) and yield more performant parts.

The “catering” budget cap breach of 2021 became a controversy not just because of money, but because in a capped era, every dollar saved on lunch is a dollar that can be deployed into the server farm.

Conclusion

When Max Verstappen lifts a trophy, he stands on a pedestal built by Detached Eddy Simulations and Hex-dominant meshes. The RB16B and its successors proved that in modern F1, the fastest car isn’t built in a wind tunnel—it’s compiled in the cloud. The championship was won 0.001 seconds at a time, long before the lights ever went out.

The invisible war continues—not with spanners and welding torches, but with Y+ calculations and turbulence models. In today’s F1, the true championship battle happens not at 200 mph on asphalt, but at the speed of light in silicon.