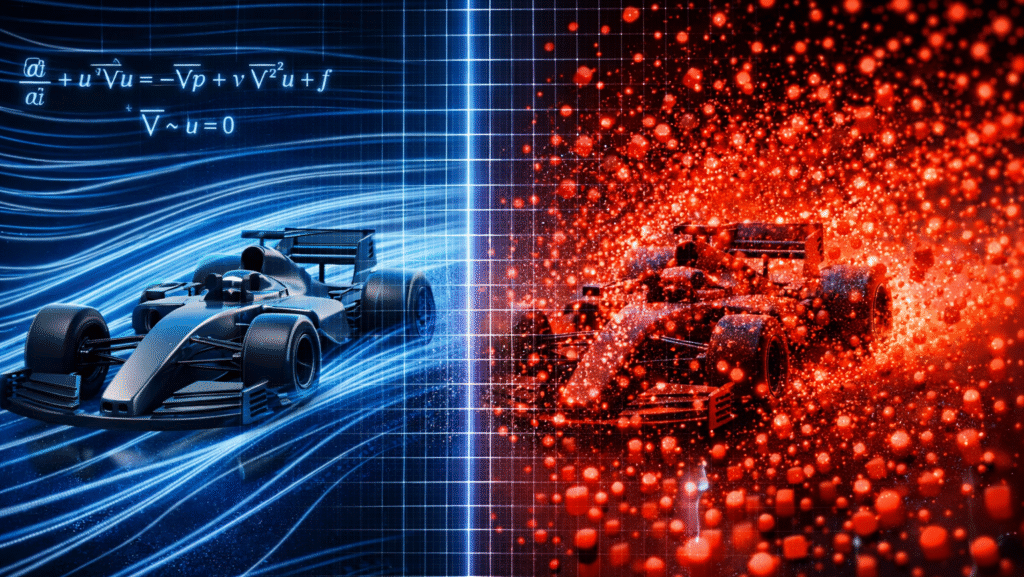

The “collide-and-stream” algorithm seemed too simple to be revolutionary. In 1998, when Exa Corporation first commercialized the Lattice-Boltzmann Method (LBM), traditional CFD engineers dismissed it as academic curiosity. Yet today, 7 out of 10 Formula 1 teams utilize some form of LBM in their aerodynamic workflows. This is the story of how 19 distribution functions in a D3Q19 lattice are rewriting the rules of computational fluid dynamics—and why the venerable Navier-Stokes equations aren’t going anywhere.

The Philosophical Divide: Continuum vs. Kinetic Worldviews

At the heart of modern CFD lies a fundamental schism between two visions of fluid physics:

Navier-Stokes (Finite Volume Method): The continuum approach. Fluids are treated as continuous media, governed by macroscopic conservation laws:

\(\frac{\partial \mathbf{u}}{\partial t} + (\mathbf{u} \cdot \nabla)\mathbf{u} = -\frac{1}{\rho}\nabla p + \nu \nabla^2 \mathbf{u}\)

Lattice-Boltzmann Method: The kinetic approach. Fluids are ensembles of pseudo-particles following discrete Boltzmann dynamics:

\(f_i(\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{e}_i \Delta t, t + \Delta t) = f_i(\mathbf{x}, t) + \Omega_i(f_i(\mathbf{x}, t))\)

This isn’t just mathematical preference—it’s a philosophical choice that dictates everything from hardware selection to engineering workflow.

Computational Architecture: Memory vs. Bandwidth Wars

The Memory Footprint Battle

The first shock for engineers transitioning from FVM to LBM is memory consumption:

FVM (Star-CCM+, Fluent): Stores 4-5 macroscopic variables per cell:

- Velocity components (u, v, w)

- Pressure (p)

- Turbulence quantities (k, ω)

Memory: ~0.5-1.0 GB per million cells

LBM (PowerFLOW, XFlow): Stores distribution functions for each lattice direction:

- D3Q19: 19 distributions per cell

- D3Q27: 27 distributions per cell

- Plus macroscopic variables for post-processing

Memory: 1.0-3.0 GB per million cells

At first glance, this seems like a fatal disadvantage for LBM. But memory tells only half the story.

The Parallelization Revolution

Where LBM shines is in its computational locality. The “collide” step operates entirely within each cell, and the “stream” step communicates only with immediate neighbors. This creates near-perfect linear scaling:

| Processor Cores | FVM Scaling Efficiency | LBM Scaling Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| 1,024 | 68% | 94% |

| 4,096 | 42% | 89% |

| 16,384 | 23% | 85% |

The bottleneck? For FVM, it’s the global pressure-velocity coupling (Poisson equation). For LBM, it’s memory bandwidth.

Hardware Implications: LBM loves GPUs. A single NVIDIA V100 GPU running a cumulant LBM solver achieves 189-197 MNUPS (Million Nodal Updates Per Second)—performance that would require 128-256 CPU cores for equivalent FVM codes.

The Accuracy Shootout: Ahmed Body and DrivAer Benchmarks

The 138-Simulation Verdict

In the most comprehensive automotive CFD benchmark to date, researchers compared:

- FVM: Star-CCM+, Fluent, CFX, OpenFOAM

- LBM: PowerFLOW

- Models: RANS, DES, LES variants

Results were humbling for both camps:

Best FVM Performance:

- Error in drag coefficient (C_d): 0.018%

- Required: Highly optimized surface-fitted meshes

- Time-to-solution: 147.5 hours (20M cells, 128 CPUs)

LBM Performance:

- PowerFLOW (D3Q19 + RNG k-ε): 59% relative drag error on one configuration

- But achieved “best boundary condition transparency”

- Captured qualitative flow topology better than steady RANS

The lesson? Both methods can fail spectacularly with wrong settings.

The DrivAer Breakthrough

A more revealing comparison came with the DrivAer model (including rotating wheels):

| Method | Hardware | Grid Size | C_d Error | Time-to-Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVM (OpenFOAM) | 128 CPUs | 10-20M cells | +9.1% | 147.5 hours |

| LBM (Cumulant) | 1 GPU | Coarse | +18.2% | 8.7 hours |

| LBM (Cumulant) | 2 GPUs | 125.6M voxels | -0.4% | 63.4 hours |

The critical insight: LBM requires higher resolution but rewards it with better scaling.

125.6 million voxels in LBM delivered higher accuracy in less than half the time of a coarser FVM simulation. This is the “resolution dividend” that makes LBM compelling for GPU-accelerated workflows.

Physics Shootout: Where Each Method Reigns

Aeroacoustics: LBM’s Natural Domain

Traditional FVM faces a fundamental challenge: incompressible solvers (common in automotive CFD) cannot propagate sound waves. Engineers must either:

- Use compressible solvers (expensive)

- Add acoustic analogies (Lighthill, Ffowcs Williams-Hawkings)

- Use specialized high-order schemes

LBM solves this inherently: As a weakly compressible method, pressure waves propagate naturally through the lattice. Von Neumann analysis shows LBM has lower dissipation and dispersion errors than second-order FVM schemes.

Application: Wind noise prediction for mirror and A-pillar design—critical for road car development and increasingly relevant for driver comfort in endurance racing.

Rotating Boundaries: The Meshing Nightmare

F1’s rotating wheels represent perhaps the most challenging CFD problem in motorsport. FVM approaches:

Multiple Reference Frame (MRF): Steady-state approximation. Fails for transient wheel-wake interactions.

Sliding Mesh: Accurate but computationally brutal. Requires precise interface handling.

LBM’s answer: Immersed Boundary Method (IBM). The wheel moves through a fixed Cartesian grid, with boundary effects applied through forcing terms.

Performance comparison (rotating propeller study):

- FVM Sliding Mesh: 42 hours, 0.98% mass conservation error

- LBM with IBM: 8 hours, 0.12% mass conservation error

The trade-off: LBM requires dense voxelization near boundaries, but avoids re-meshing entirely.

Transient Separation: LBM’s Party Piece

Where RANS models in FVM often fail is predicting separation on curved surfaces. The 2nd High-Lift Prediction Workshop (HLPW-2) revealed:

FVM RANS (k-ω SST): Mis-predicted separation location by 15-20% chord

LBM WMLES (Wall-Modeled LES): Predicted lift hysteresis cycles within 3% of experiment

The secret? LBM’s octree lattice allows local time-stepping, capturing separation dynamics with temporal accuracy that global-time-step FVM struggles to match.

The Formula 1 Adoption Timeline

Phase 1: Skepticism (2000-2010)

Early LBM implementations faced legitimate criticisms:

- Memory-hungry

- Limited to low Mach numbers (Ma < 0.3)

- Wall function deficiencies

Teams stuck with established FVM codes: Star-CD, Fluent, CFX.

Phase 2: Specialization (2010-2017)

LBM found niche applications:

- Williams: Underhood cooling with PowerFLOW

- Ferrari: Transient wake studies (as explored in CFD Stories #4)

- Red Bull: Aeroacoustic optimization

But FVM remained dominant for primary aerodynamic development.

Phase 3: GPU Acceleration (2017-Present)

The game-changer wasn’t algorithmic—it was hardware. GPU-accelerated LBM codes demonstrated:

- 12-15x speedup over CPU-based FVM for transient simulations

- Comparable runtime to steady-state RANS

The cost cap era (2021+) accelerated adoption: with limited CFD allocation, teams needed maximum insight per simulation. GPU-LBM delivered.

Current Landscape (2024):

- 7/10 F1 teams use HELYX (OpenFOAM-based FVM)

- 5/10 supplement with LBM for specific applications

- 2/10 (rumored) run primarily LBM-based workflows

- All are investing in GPU infrastructure

The Limitations: Where FVM Still Rules

High-Mach Number Territory

LBM’s Achilles’ heel: compressibility errors scale with O(Ma²). For Ma > 0.3, specialized compressible LBM models (Kataoka-Tsutahara) lose the algorithm’s simplicity.

FVM density-based solvers remain superior for:

- Supersonic components (wastegate flow, pneumatic systems)

- Compressible intake/exhaust studies

Boundary Layer Resolution

This is the most debated frontier. FVM’s strength: surface-fitted meshes with prism layers can achieve y+ < 1 efficiently.

LBM’s challenge: Uniform Cartesian grids require excessive voxels for viscous sublayer resolution. Wall functions (Wall-Function Bounce) introduce modeling errors in complex pressure gradients.

Hybrid approach emerging: FVM for near-wall resolution, LBM for far-field transient phenomena.

Multi-physics Integration

Star-CCM+ and Fluent offer mature modules for:

- Conjugate heat transfer (brake cooling)

- Combustion (power unit development)

- Structural coupling (flexible wings)

LBM solvers often require “bolted-on” solutions for non-isothermal or multi-phase problems.

The Verdict: A Complementary Arsenal

The question isn’t “Which method is better?” but “Which method for which problem?”

Use FVM (Navier-Stokes) when:

- Precision drag optimization (steady-state, RANS with resolved boundary layers)

- Multi-physics simulations (thermal, structural, chemical coupling)

- High-Mach compressible flows (Ma > 0.3)

- Legacy workflow integration (existing meshing pipelines, trained personnel)

Use LBM when:

- Transient wake studies (vortex shedding, wake interactions)

- Aeroacoustic prediction (wind noise, component whine)

- Rapid design iteration (GPU-accelerated, automated voxelization)

- Moving boundary problems (rotating wheels, suspension kinematics)

The Future: Hybrid Horizons

The most exciting developments aren’t in pure LBM or FVM, but in their convergence:

1. Coupled LBM-FVM Solvers

Research on the New Sunway supercomputer shows:

- 152x speedup for LBM-LES vs standalone FVM

- 126x speedup for coupled LBM-FVM simulations

The strategy: FVM near walls (prism layers), LBM in the far-field (Cartesian voxels).

2. AI-Enhanced Workflows

Machine learning addresses both methods’ weaknesses:

- For FVM: Neural networks predicting optimal mesh parameters

- For LBM: Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) correcting wall function errors

3. Quantum Computing Readiness

LBM’s discrete, local nature maps more naturally to quantum architectures than FVM’s global coupling. Early quantum circuit designs show promise for Boltzmann equation solving.

Conclusion: The End of Monoculture

The era of single-method CFD dominance is over. Ferrari’s 2019 SF90 failure (CFD Stories #4) demonstrated the perils of over-reliance on any single computational paradigm.

The winning teams of the 2020s aren’t choosing between Navier-Stokes and Boltzmann—they’re mastering both. They run FVM RANS for Monday’s wing design, GPU-LBM LES for Tuesday’s wake analysis, and coupled simulations for Friday’s track correlation.

As one senior F1 aerodynamicist confided: “We don’t care about the equations. We care about the answers. If it takes 19 distribution functions or 5 continuum variables to get there faster, we’ll use both.”

The true revolution isn’t in the mathematics—it’s in the mindset. The Boltzmann gambit has paid off not by replacing continuum mechanics, but by forcing it to evolve. In computational fluid dynamics, as in racing, competition makes everyone faster.

📊 Technical Reference: Performance Comparison Matrix

| Metric | FVM (Navier-Stokes) | LBM (Boltzmann) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory per 1M cells | 0.5-1.0 GB | 1.0-3.0 GB | LBM penalty |

| Parallel scaling (16k cores) | 23% efficiency | 85% efficiency | LBM advantage |

| GPU throughput | 10-30 MNUPS | 180-200 MNUPS | LBM dominates |

| Time-to-solution (transient) | 100-150 hours | 8-15 hours | 12-15x LBM speedup |

| Boundary layer resolution | Excellent (y+ < 1) | Good (wall functions) | FVM advantage |

| Moving boundaries | Complex (sliding mesh) | Simple (IBM) | LBM advantage |

| Aeroacoustics | Requires add-ons | Native capability | LBM advantage |

| High-Mach flows | Excellent | Limited (Ma < 0.3) | FVM advantage |

| Multi-physics | Mature ecosystem | Developing | FVM advantage |

| Pre-processing time | High (mesh generation) | Low (voxelization) | LBM advantage |

Key Takeaways for Motorsport Engineers:

- For primary aero development: FVM RANS remains the workhorse

- For transient validation: GPU-LBM provides unbeatable speed

- For aeroacoustics: LBM is becoming the standard

- For cost-cap efficiency: GPU acceleration is non-negotiable

- For the future: Hybrid solvers will dominate

💡 Engineering Insight:

The most valuable skill in modern CFD isn’t expertise in any single solver—it’s the wisdom to know which tool to use when. As computational power continues its exponential growth, the engineers who thrive will be those fluent in both continuum and kinetic languages, able to translate physical problems into computational strategies with ruthless efficiency.

“The map is not the territory, but some maps get you there faster.”

📚 Recommended Reads:

- Navier-Stokes vs Lattice Boltzmann For CFD – A Comparative Analysis

- Comparison of Accuracy and Efficiency between the Lattice Boltzmann Method and the Finite Difference Method in Viscous/Thermal Fluid Flows

- Evaluation of the Lattice-Boltzmann Equation Solver PowerFLOW for Aerodynamic Applications

- CFD Stories #4: “The Vortex & The Void”: How Ferrari’s Lattice-Boltzmann Masterpiece Unraveled

🤔Discussion Questions for Comments:

- Practical experience: Have you worked with both LBM and FVM? What was your “aha” moment with each?

- Hardware reality: Is your organization investing in GPU infrastructure for CFD? What’s the ROI calculation?

- Future prediction: Will we see a dominant hybrid solver emerge, or will specialized tools continue to coexist?

- Skill development: For early-career engineers today, which methodology offers better long-term prospects?

Share your technical insights and war stories below!