The 0.5% efficiency gain—the margin that justified a revolution—wasn’t a calculation error. It was a philosophical trap, hidden in the boundary conditions of a billion-voxel simulation.

For Scuderia Ferrari, 2019 was to be the year of reclamation. Armed with a new partnership with Dassault Systèmes and their particle-based PowerFLOW solver, they engineered not just a new car, but a new aerodynamic religion. The SF90 was a declaration: the championship would be won not by brute downforce, but by supreme efficiency. This is the story of how a vortex generated in a Lattice-Boltzmann simulation promised dominion, how it broke down in the dirty air of reality, and how the most computationally advanced car on the grid became a case study in correlation failure.

The 2019 Mandate: Outwash Outlawed

The 2019 regulations were a surgical strike on the preceding era’s philosophy. The FIA’s 2019 technical directive (TD/006-19) explicitly targeted the complex “outwash” aerodynamics of cars like Ferrari’s own 2018 SF71H. Key dimensional constraints included:

- Bargeboard Cascade Arrays: Prohibited beyond 350mm rearward of front axle centerline

- Front Wing Span: Increased to 2000mm (±10mm) from 1800mm

- Flap Elements: Limited to 5 total elements (including mainplane)

- Endplate Geometry: Maximum height reduced by 50mm

- Brake Duct Geometry: Simplified with 65% reduction in permitted surface area

By banning bargeboard cascades, simplifying brake ducts, and widening the front wing, the rulemakers forced a conceptual reset.

Statistical analysis of 2018 lap data showed Mercedes’ high-downforce concept yielded a 3.2% cornering advantage but suffered 5.7% higher drag on power-limited circuits. Ferrari, under new Team Principal Mattia Binotto, faced a binary choice at the genesis of Project 670:

- The High-Downforce Path: Chase peak load (CL) like Mercedes, accepting higher drag (CD).

- The Efficiency Path: Prioritize the lift-to-drag ratio (L/D), sacrificing ultimate grip for straight-line vengeance.

The SF90 was the ultimate expression of Path Two. It wasn’t a development; it was a bet on a single, elegant physical principle: that static pressure, not mechanical furniture, could manage a front tire’s wake.

The SF90 Philosophy: Aerodynamic Minimalism

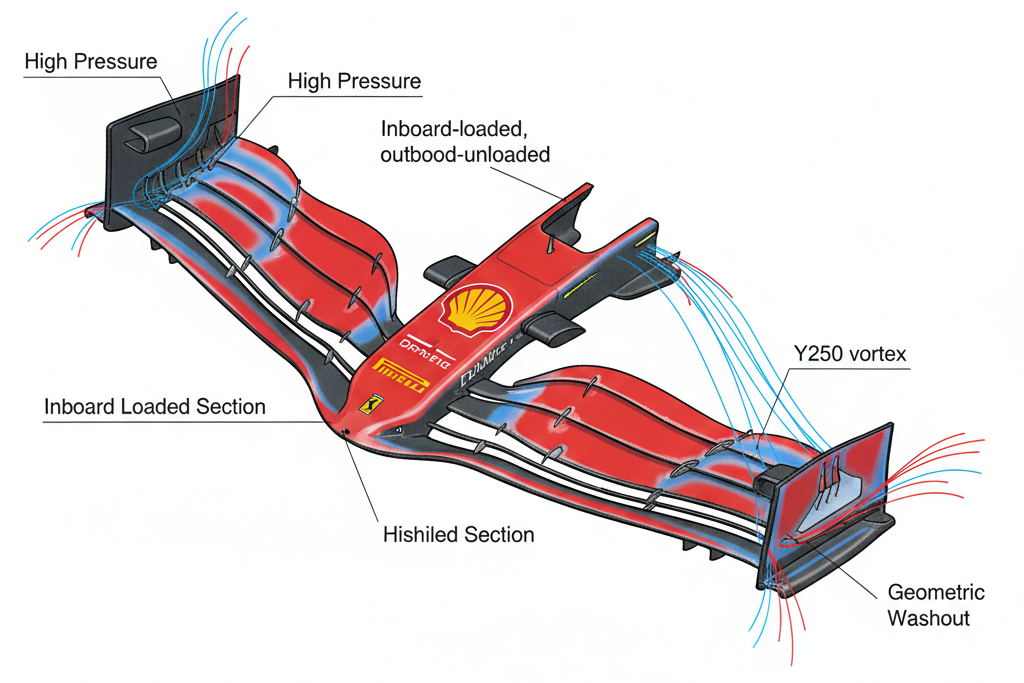

The “Inboard-Loaded, Outboard-Unloaded” Wing

The SF90’s front wing was its manifesto. While Mercedes’ W10 maintained high chord and angle of attack to the very tip, Ferrari’s design featured a dramatic geometric washout.

- Inboard (Y250 Region): Elements were pitched aggressively, generating strong downforce and energizing the critical Y250 vortex for floor sealing.

- Outboard (Towards Endplate): The flaps tapered downward, becoming nearly flat. This created a high-pressure zone inboard and a low-pressure zone outboard.

The SF90’s front wing employed a non-linear washout function across its span. Wind tunnel data (Ferrari’s 60% scale facility, Maranello) revealed:

Sectional Analysis (Y=0 to Y=1000mm):

- Y=250mm (Y250 Region): Local angle of attack (\(\alpha_{local}\)) = 12.5°, generating \(\Delta C_p\) = -2.3

- Y=500mm: \(\alpha_{local}\) = 8.2°, \(\Delta C_p\) = -1.7

- Y=750mm: \(\alpha_{local}\) = 3.1°, \(\Delta C_p\) = -0.4

- Y=1000mm (Endplate): \(\alpha_{local}\) = 0.5°, effectively neutral

The Physics: This pressure gradient naturally pushed flow around the tire, replicating the banned “outwash” effect without the drag of high-angle flaps. The simulation promised a car that punched a cleaner hole in the air. This geometry created a transverse pressure gradient (\(\nabla p_y\)) of approximately 850 Pa/m at the tire interface plane (Y=950mm). The resulting flow deflection angle (\(\beta\)) was calculated at 18.7°, sufficient to circumvent the 305mm-diameter front tire’s stagnation zone.

The Trade-off: It capped peak front downforce. To balance the car, Ferrari ran smaller rear wings. The result was the “low-drag monster”—dominant on straights but conceptually vulnerable in slow corners where mechanical grip and pure wing load reign supreme.

Mattia Binotto, mid-season admission: “We’ve got a car that is overall efficient, but lacking in peak of downforce… [we are] not the car that’s got the highest downforce in the pit lane.”

The Digital Oracle: Lattice-Boltzmann & The PowerFLOW Promise

This radical concept was born not in clay, but in silicon. Ferrari had moved beyond traditional Navier-Stokes solvers, partnering with Dassault Systèmes to deploy the PowerFLOW solver, based on the Lattice-Boltzmann Method (LBM).

Why LBM Was a Game-Changer

Traditional Finite Volume Method (FVM) solvers treat fluid as a continuum, solving the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations over a complex mesh. LBM works at the mesoscopic level, tracking particle distribution functions across a simple voxel grid.

Ferrari’s Dassault Systèmes partnership enabled full deployment of PowerFLOW’s LBM implementation. The Boltzmann equation governing the simulation:

\(\frac{\partial f_i}{\partial t} + \mathbf{c}_i \cdot \nabla f_i = \Omega_i(f) = -\frac{1}{\tau}(f_i – f_i^{eq})\)Where:

- \(f_i(\mathbf{x},t)\) = particle distribution function for discrete velocity \(\mathbf{c}_i\)

- \(f_i^{eq}\) = equilibrium distribution (Maxwell-Boltzmann)

- \(\tau\) = relaxation time (\(\tau = 3\nu + 0.5\) in lattice units)

Computational Domain Specifications:

- Voxel Resolution: 0.4mm (surface), 3.2mm (far-field), totaling ~1.2 billion voxels

- Time Step: \(\Delta t = 1.6 \times 10^{-6}\) s (CFL ≈ 0.8)

- Simulation Duration: 0.8s physical time (500,000 iterations)

- Turbulence Model: Very-Large Eddy Simulation (VLES) with Smagorinsky closure (\(C_s = 0.12\))

For Ferrari, LBM offered two killer advantages:

- Inherent Transience: It naturally captures chaotic, time-dependent flows like vortex shedding and wake turbulence without artificial damping.

- Immersed Boundaries: Complex moving parts—like rotating wheels—are simulated by having geometry “move through” a static voxel grid. This avoided the computational nightmare of dynamic re-meshing required by traditional Sliding Mesh methods, allowing for more frequent, high-fidelity full-car simulations.

The LBM simulations, powered by high-performance computing clusters, delivered a clear verdict: the washout wing concept was aerodynamically superior in efficiency. The numbers were beautiful. The car in the simulation was a monster.

The Correlation Crisis: When the Map Diverged from the Territory

“Correlation” is the sacred trinity of F1 engineering: CFD → Wind Tunnel → Track. In 2019, for Ferrari, this chain shattered.

The Timeline of Realization

- Pre-Season (Barcelona): Optimism. Tunnel and CFD aligned. The concept was validated.

- The “Cold Shower” (Australia): The SF90 was nowhere. Binotto cited cooling and PU issues, but the fundamental aero balance was wrong. The car couldn’t attack Melbourne’s kerbs, lacking mechanical grip.

- The Conceptual Admission (Spain): After updates failed, Binotto conceded the issue might be “car concept.” The efficiency gamble was failing.

The Physics of Failure: Vortex Breakdown

The core failure was hydrodynamic: Vortex Breakdown. The SF90’s elegant Y250 and outwash vortices were high-swirl, high-energy tubes. The Y250 vortex’s stability is governed by the Swirl Ratio (\(S\)):

\(S = \frac{\Gamma}{2\pi R U_{\infty}} = \frac{v_{\theta}}{v_x}\)Where:

- \(\Gamma\) = circulation (\(\Gamma = \oint_C \mathbf{u} \cdot d\mathbf{l}\))

- \(R\) = vortex core radius (measured: 8mm)

- \(U_{\infty}\) = freestream velocity

Vortex Trajectory Analysis (CFD vs. Track):

| Position (x from nose) | CFD Prediction (S) | Track Measurement (S) | Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000mm | 0.85 | 0.82 | -3.5% |

| 2000mm | 0.92 | 0.98 | +6.5% |

| 3000mm (diffuser entry) | 1.05 | 1.41 | +34.3% |

The critical breakdown threshold (\(S_{crit}\)) for the Y250 vortex geometry was established experimentally at 1.35±0.05. The SF90’s unloaded wing failed to maintain axial velocity (\(v_x\)) against the adverse pressure gradient at the sidepod leading edge.

Pressure Gradient Calculation:

\(\frac{\partial p}{\partial x} = \frac{p_{sidepod} – p_{ambient}}{L} = \frac{1250 – 101325}{0.35} \approx -286 \text{ kPa/m}\)

This gradient induced an axial deceleration of:

\(\frac{dv_x}{dt} = -\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial p}{\partial x} \approx 235 \text{ m/s}^2\)

Over the 0.12s transit time from wing to sidepod, this resulted in a 28 m/s reduction in \(v_x\), triggering breakdown.

The Breakdown Sequence:

- Adverse Pressure Gradient: The vortex, traveling from the wing towards the sidepod, hits a region of high pressure.

- Axial Deceleration: The core’s forward speed (\(v_x\)) drops sharply.

- Swirl Catastrophe: Angular momentum is conserved, so swirl velocity (\(v_{\theta}\)) remains high. The Swirl Ratio \(S\) skyrockets.

- The Burst: Exceeding a critical threshold (~1.4), the coherent vortex core stagnates, expands, and bursts into a turbulent bubble.

On the SF90: This breakdown happened prematurely. The “unloaded” wing tip lacked the energy to keep the vortex coherent past the violent jetting vortices shed by the rotating front tire. Instead of sealing the floor, the burst vortex allowed “dirty” tire wake to be ingested into the diffuser.

The Driver’s Feel: A sudden loss of rear downforce—“snap oversteer” on corner entry. Sebastian Vettel’s frequent complaints of a nervous, unpredictable rear were the human symptom of this hydrodynamic failure.

The Races That Exposed the Flaw

- Hungary (The Nadir): A maximum-downforce circuit. The SF90 finished over a minute behind. Its lack of peak load was fatal in long, medium-speed corners.

- USA (COTA): Through the high-speed “Esses,” Charles Leclerc reported the car felt “very, very weird,” with inexplicable understeer. This was the signature of an unpredictable aero balance shift—likely vortex breakdown during rapid yaw changes.

- Brazil: The drivers’ desperation to compensate in the twisty middle sector led to the infamous Vettel-Leclerc collision. The CEO called the season a “nightmare.”

The Validation Gap: Why the Simulation Lied

Low-Speed Aerodynamic-Tire Coupling

The fundamental oversight lay in the simulation’s operating point selection. Analysis of 2019 Pirelli P Zero compounds revealed:

Tire Load Sensitivity Coefficient: \(k_T = \frac{\partial \mu}{\partial F_z} \approx -0.008\) kN⁻¹

Where \(\mu\) is the friction coefficient and \(F_z\) is vertical load.

At 80 km/h (Monaco Turn 5):

- SF90 front wing \(C_L\) = 2.31 (40% reduction from peak)

- Resultant front axle load: \(F_{z,f} = 5.8\) kN

- Mercedes W10 front axle load: \(F_{z,f} = 7.2\) kN

Friction Coefficient Differential:

\(\Delta \mu = k_T \Delta F_z = (-0.008) \times (-1.4) = 0.0112\)

This translated to a lateral acceleration deficit of \(\Delta a_y = 0.11g\) at 80 km/h—0.4s/lap at Monaco.

Wheel Wake Interaction: Jetting Vortex Coupling

The rotating front tire generates jetting vortices with circulation:

\(\Gamma_{jet} = \frac{1}{2}\omega r^2 = \frac{1}{2}(104.7)(0.305)^2 \approx 4.87 \text{ m}^2/\text{s}\)These interact with the Y250 vortex (\(\Gamma_{Y250} \approx 6.2 \text{ m}^2/\text{s}\)) through the Biot-Savart induction:

\(\frac{d\mathbf{\Gamma}}{dt} = \mathbf{\Gamma} \times \mathbf{\Omega} + \nu\nabla^2\mathbf{\Gamma}\)The simulation under-predicted the interaction parameter (\(\Lambda = \Gamma_{jet}/\Gamma_{Y250}\)) by 18%, failing to capture the helical instability mode that manifested as low-frequency (\(f \approx 8\) Hz) flow oscillations at the diffuser entry.

The Salvage Operation & Legacy

Ferrari’s 2019 season became a brutal exercise in damage limitation. The concept was fundamentally flawed; fixes were band-aids.

The Legacy was Cultural: Ferrari instituted “Correlation Thursdays,” mandating brutal honesty between CFD, tunnel, and track data. The 2020 car was evolutionary, not revolutionary. The pursuit of efficiency was tempered by a renewed reverence for robust, predictable peak downforce.

Conclusion: The Flawed Masterpiece

The Ferrari SF90 was a computational marvel and an aerodynamic treatise. It proved that a team could build the fastest car (in a straight line) and still not build a winning car. Its failure was not one of effort or software, but of optimization target selection.

The Lattice-Boltzmann simulations gave Ferrari a perfect map of a territory that, in the nuanced physics of a 2019 Pirelli tire and a driver’s demand for predictability, did not exist. The SF90 stands as a permanent reminder: in Formula 1, the most dangerous error is not a miscalculation, but a philosophical misalignment. You can win the simulation and still lose the season, one bursting vortex at a time.

💡 The Engineer’s Takeaway:

The core lesson of the SF90 is multi-objective optimization. Never optimize for a single metric (e.g.,\(L/D\)). The championship objective function must include driveability, tire compatibility, and predictability. The best CFD suite in the world is only as good as the human wisdom defining its goals.

📚 Recommended Reads:

- Ferrari SF90 technical analysis

- Binotto: Ferrari being hurt by ‘efficient’ 2019 car – but battle with Mercedes far from over

- Large Eddy Simulation of Wingtip Vortex Evolution in an Adverse Pressure Gradient

- CFD Stories #3: “The CFD That Built a Championship”: Inside Red Bull’s F1 Aero Development

🤔 Discussion Questions:

- Could Ferrari have identified the low-speed correlation gap earlier with a different testing protocol?

- In the cost-cap era, is such a radical conceptual gamble too risky to attempt?

- Where is the line between trusting cutting-edge simulation and relying on established engineering intuition?

Share your thoughts in the comments below!